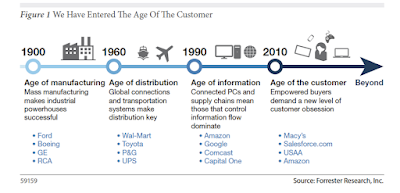

Back in 2013, Forrester Research declared a new business era that they called the Age of the Customer. In this new era, empowered customers demand a new level of customer service that provides a source of dominance to companies delivering that kind of service. Realizing that, terms like customer success, customer journey, and customer obsession started to emerge. We even coined new metrics such as CSAT score and NPS.

What was behind this customer obsession was the fear that customers, armed with their Twitter and Facebook accounts, have gained an unprecedented amount of power. This power was ready to be unleashed against companies that disappointed their expectations. The Twitter mobs were feared, and there were plenty of examples of this happening. Perhaps you remember the once-famous United Breaks Guitars song? So, let’s fast forward ten years and examine how things panned out.

Well, not at all how Forrester predicted it.

Sure, there are a few examples of companies that truly demonstrate customer obsession by placing customers over short-term profits. Frequently named examples include Southwest Airlines, Nordstrom, and Amazon. But those companies had figured out the customer obsession game long before the threat of Twitter mobs. In truth, most companies have gone backward on their customer-centricity.

For example, retail companies have installed self-checkout kiosks to reduce labor costs, and the remaining staff are responsible for restocking shelves rather than talking to customers. Restaurants are paying more attention to their online orders than to the customers sitting at a table. And airlines... does anyone believe that airlines care about their customers? Their greatest innovation in the last 10 years was Basic Economy with poorer customer service than the Standard Economy.

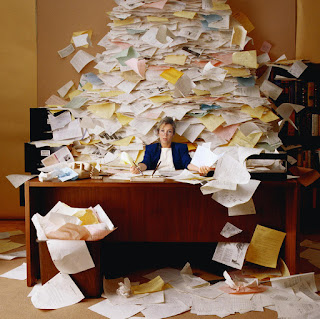

In the online world, things are not any better. Most companies are doing what it takes to prevent customer contact. There is even a new term for not having to talk to customers: “call deflection.” In order to deflect those pesky customer requests, companies often no longer publish their phone number and force customers to help themselves. Self-service has become their mantra as they make the customer responsible for buying, deploying, and fixing the product on their own. Most importantly, companies are spending thousands of dollars on technology that is supposed to answer customers' questions.

This technology comes typically in the form of software such as knowledge base and chatbots. The chatbots are particularly popular as they are usually good enough to answer some basic customer questions. The trouble is that most customers resort to contacting the company only when they are stuck with a not-so-basic problem. Too bad! If you are lucky, the chatbot eventually discloses the secret phone number to call a human. You then have to pass through the frustrating voice-based menu, spend 45 minutes on hold, only to eventually speak to someone offshore who is measured on how quickly they get rid of you.

This trend impacts even generative AI, the technology that has been at the center of the latest hype in Silicon Valley and beyond. Today, the killer app for generative AI is customer service. That really means smarter chatbots that will enable companies to deflect even more customer calls. The end goal is the reduction of labor cost by not having any direct human contact with customers in the Service and Support departments.

As you can tell, I am not impressed by what has become of the Age of the Customer. What really happened is that social media has lost a lot of its power as the customer megaphone. Complaining about poor customer service today is seen as a rant with little or no impact on the company’s reputation. Seeing the feared weapon much weakened, companies reverted to good old greed.

In addition, many companies confuse understanding their customers with customer centricity. While delving into customer data and optimizing the business based on these insights is important, it usually results in a company-centric optimization rather than customer-centricity. True customer-centric behavior requires prioritizing customers above short-term profits, with the conviction that profits will eventually follow. However, this approach takes guts, perseverance, and a long-term horizon – qualities that very few managers are measured on.

I still believe that taking good care of customers is one of the most powerful competitive differentiators any company can deploy. Zappos is a good example of that. By letting customers order and return merchandise as many times as they want, Zappos has clearly put its immediate profits second to the concern for customer satisfaction. It worked. But sadly, there are only a few examples of companies like that.